Main article: Jain philosophy

| Part of a series on |

| Jain philosophy |

|---|

| Concepts |

|

| People |

|

Dravya ("Substance")[edit]

Main article: Dravya

According to Jainism, there are six simple substances in existence: Soul, Matter, Time, Space, Dharma and Adharma.[69] Jain philosophers distinguish a substance from a body (or thing) by declaring the former to be a simple element or reality and the latter a compound of one or more substances or atoms. They claim that there can be a partial or total destruction of a body or thing, but no substance can ever be destroyed.[70] According to Champat Rai Jain:

Jīva ("Soul")[edit]

Main article: Jīva (Jainism)

Jain philosophy is the oldest Indian philosophy that completely separates body (matter) from the soul (consciousness).[72] Jains maintain that all living beings are really soul, intrinsically perfect and immortal. Souls in saṃsāra (that is, liability to repeated births and deaths) are said to be imprisoned in the body.[73]

The soul-substance, called Jīva in Jainism, is distinguished from the remaining five substances (Matter, Time, Space, Dharma and Adharma), collectively called ajīva, by the intelligence with which the soul-substance is endowed, and which is not found in the other substances.[70] The nature of the soul-substance is said to be freedom. In its modifications, it is said to be the subject of knowledge and enjoyment, or suffering, in varying degrees, according to its circumstances.[74] Jain texts expound that all living beings are really soul, intrinsically perfect and immortal. Souls in transmigration are said to be embodied in the body as if in a prison.[75]

Ajīva ("Non-Soul")[edit]

Main article: Ajiva

- Matter (Pudgala) is considered a non-intelligent substance consisting of an infinity of particles or atoms which are eternal. These atoms are said to possess sensible qualities, namely, taste, smell, color and, in certain forms, touch and sound.[76][74]

- Time is said to be the cause of continuity and succession. It is of two kinds: nishchaya and vyavhāra.[77]

- Space (akāśa)- Space is divided by the Jainas into two parts, namely, the lokākāśa, that is the space occupied by the universe, and the alokākāśa, the portion beyond the universe. The lokākāśa is the portion in which are to be found the remaining five substances, i.e., Souls, Matter, Time, Dharma and Adharma; the alokākāśa is the region of pure space containing no other substance and lying stretched on all sides beyond bounds of the three worlds (the entire universe).[78]

- Dharma and Adharma are substances said to be helpful in the motion and stationary states of things, respectively - the former enabling them to move from place to place and the latter to come to rest from the condition of motion.[77]

Tattva ("Reality")[edit]

Main article: Tattva (Jainism)

Jain philosophy is based on seven fundamentals which are known as tattva, which attempt to explain the nature of karmas and provide solutions for the ultimate goal of liberation of the soul (moksha):[79] These are:[80]

- Jīva – the soul, which is characterized by consciousness

- Ajīva – non-living entities that consist of matter, space and time

- Āsrava ("influx") – the inflow of auspicious and evil karmic matter into the soul

- Bandha ("bondage") – mutual intermingling of the soul and karmas. The karma masks the jiva and restricts it from reaching its true potential of perfect knowledge and perception.

- Saṃvara ("stoppage") – obstruction of the inflow of karmic matter into the soul

- Nirjarā ("gradual dissociation") – the separation or falling off of part of karmic matter from the soul

- Moksha ("liberation") – complete annihilation of all karmic matter (bound with any particular soul)

Soul and Karma[edit]

Main article: Karma in Jainism

According to Jain belief, souls, intrinsically pure, possess the qualities of infinite knowledge, infinite perception, infinite bliss, and infinite energy in their ideal state.[81] In reality, however, these qualities are found to be obstructed due to the soul's association with karmic matter.[82] The ultimate goal in Jainism is the realisation of reality.[83]

The relationship between the soul and karma is explained by the analogy of gold. Gold is always found mixed with impurities in its natural state. Similarly, the ideal pure state of the soul is always mixed with the impurities of karma. Just like gold, purification of the soul may be achieved if the proper methods of refining are applied.[82] The Jain karmic theory is used to attach responsibility to individual action and is cited to explain inequalities, suffering, and pain. Tirthankara-nama-karma is a special type of karma, bondage of which raises a soul to the supreme status of a tirthankara.[84]

Vitalism[edit]

Main article: Vitalism (Jainism)

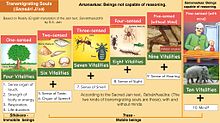

Jain texts state that there are ten vitalities or life-principles: the five senses, energy, respiration, life-duration, the organ of speech, and the mind.[8] The table below summarizes the vitalities that living beings possess in accordance with their senses.[85]

| Senses | Number of vitalities | Vitalities |

|---|---|---|

| One-sensed beings | Four | Sense organ of touch, strength of body or energy, respiration, and life-duration. |

| Two-sensed beings | Six | The sense of taste and the organ of speech in addition to the former four. |

| Three-sensed beings | Seven | The sense of smell in addition to the former six. |

| Four-sensed beings | Eight | The sense of sight in addition to the former seven. |

| Five-sensed beings | Nine | The sense of hearing in addition to the former eight. |

| Ten | Mind in addition to the above-mentioned nine vitalities. |

Cosmology[edit]

Main article: Jain cosmology

Jain texts propound that the universe was never created, nor will it ever cease to exist. It is independent and self-sufficient, and does not require any superior power to govern it. Elaborate descriptions of the shape and function of the physical and metaphysical universe, and its constituents, are provided in the canonical Jain texts, in commentaries, and in the writings of the Jain philosopher-monks.[86][87]

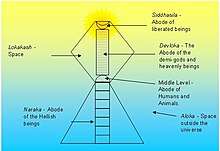

According to the Jain texts, the universe is divided into three parts, the upper, middle, and lower worlds, called respectively urdhva loka, madhya loka, and adho loka.[88] It is made up of six constituents: Jīva, ("the living entity"); Pudgala, ("matter"); Dharma tattva, ("the substance responsible for motion"); Adharma tattva, ("the substance responsible for rest"); Akāśa, ("space"); and Kāla, ("time").[89]

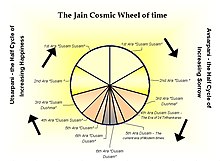

Kāla ("time") is without beginning and eternal;[69] the cosmic wheel of time, called kālachakra, rotates ceaselessly. According to Jain texts, in this part of the universe, there is rise and fall during the six periods of the two aeons of regeneration and degeneration.[90] Thus, the worldly cycle of time is divided into two parts or half-cycles, ascending utsarpiṇī ("ascending") and avasarpiṇī ("descending").[69] Utsarpiṇī is a period of progressive prosperity, where happiness increases, while avasarpiṇī is a period of increasing sorrow and immorality.[91][92] According to Jain cosmology, it is currently the 5th ara of avasarpiṇī (half time cycle of degeneration). As of 2016, exactly 2,538 years have elapsed, and 18,460 years are still left.[93] The present age is one of sorrow and misery. In this ara, though religion is practised in lax and diluted form, no liberation is possible. At the end of this ara, even the Jain religion will disappear,[93] only to appear again with the advent of the first Tīrthankara after the 42,000 years of next utsarpiṇī are over.[94]

The following table depicts the six aras of avasarpiṇī[95]

| Name of the Ara | Degree of happiness | Duration of Ara | Average height of people | Average lifespan of people |

| Sukhama-sukhamā | Utmost happiness and no sorrow | 400 trillion sāgaropamas | Six miles tall | Three palyopama years |

| Sukhamā | Moderate happiness and no sorrow | 300 trillion sāgaropamas | Four miles tall | Two palyopama Years |

| Sukhama-dukhamā | Happiness with very little sorrow | 200 trillion sāgaropamas | Two miles tall | One palyopama years |

| Dukhama-sukhamā | Happiness with little sorrow | 100 trillion sāgaropamas | 1500 meters | 705.6 quintillion years |

| Dukhamā | Sorrow with very little Happiness | 21,000 years[96] | 6 feet | 130 years maximum |

| Dukhama- dukhamā | Extreme sorrow and misery | 21,000 years | 2 feet | 16–20 years |

This trend will start reversing at the onset of utsarpinī kāl with the Dukhama-dukhamā ara being the first ara of utsarpinī (half-time cycle of regeneration).[95]

According to Jain texts, sixty-three illustrious beings, called śalākāpuruṣas, are born on this earth in every Dukhama-sukhamā ara.[97] The Jain universal history is a compilation of the deeds of these illustrious persons.[98] They comprise twenty-four Tīrthaṅkaras, twelve chakravartins, nine balabhadra, nine narayana, and nine pratinarayana.[99][97]

A chakravartī is an emperor of the world and lord of the material realm.[97] Though he possesses worldly power, he often finds his ambitions dwarfed by the vastness of the cosmos. Jain puranas give a list of twelve chakravartins ("universal monarchs"). They are golden in complexion.[100] One of the greatest chakravartins mentioned in Jain scriptures is Bharata Chakravartin. Jain texts like Harivamsa Purana and Hindu Texts like Vishnu Purana mention that India came to be known as Bharatavarsha in his memory.[101][102]

There are nine sets of balabhadra, narayana, and pratinarayana. The balabhadra and narayana are brothers.[103] Balabhadra are nonviolent heroes, narayana are violent heroes, and pratinarayana can be described as villains. According to the legends, the narayana ultimately kill the pratinarayana. Of the nine balabhadra, eight attain liberation and the last goes to heaven. On death, the narayana go to hell because of their violent exploits, even if these were intended to uphold righteousness.[104]

Epistemology[edit]

Main article: Jain epistemology

In Jainism, jnāna ("knowledge") is said to be of five kinds—Kevala Jnana ("Omniscience"), Śrutu Jñāna ("Scriptural Knowledge"), Mati Jñāna ("Sensory Knowledge"), Avadhi Jñāna ("Clairvoyance"), and Manah prayāya Jñāna ("Telepathy").[105] According to the Jain text Tattvartha sutra, the first two are indirect knowledge and the remaining three are direct knowledge.[106] Jains maintain that knowledge is the nature of the soul. According to Champat Rai Jain, "Knowledge is the nature of the soul. If it were not the nature of the soul, it would be either the nature of the not-soul, or of nothing whatsoever. But in the former case, the unconscious would become the conscious, and the soul would be unable to know itself or any one else, for it would then be devoid of consciousness; and, in the latter, there would be no knowledge, nor conscious beings in existence, which, happily, is not the case."[107]

Liberation and Godhood[edit]

Main article: Moksha (Jainism)

The Path to Liberation[edit]

Main article: Ratnatraya

- Samyak darśana ("Right View")– Belief in substances like soul (Jīva) and non-soul without delusions.[109]

- Samyak jnana ("Right Knowledge" – Knowledge of the substances (tattvas) without any doubt or misapprehension.[110]

- Samyak charitra (Right Conduct) – Being free from attachment, a right believer does not commit hiṃsā (injury).[111]

According to the Jain text, Sarvārthasiddhi, (translated by S. A. Jain):

Stages on the Path[edit]

Main article: Gunasthana

In Jain philosophy, the fourteen stages through which a soul must pass in order to attain liberation (moksha) are called Gunasthāna.[113][114][115] These are:[116]

| Gunasthāna | Explanation |

|---|---|

| 1. Mithyātva | Gross ignorance. The stage of wrong believer |

| 2. Sasādana | Vanishing faith, i.e., the condition of the mind while actually falling down from the fourth stage to the first stage.[117] |

| 3. Mishradrshti | Mixed faith and false belief.[117] |

| 4. Avirata samyagdrshti | Right Faith unaccompanied by Right Conduct.[118] |

| 5. Deśavirata | The stage of partial self-control (Śrāvaka)[118] |

| 6. Pramatta Sanyati | First step of life as a Jain muni (monk).[118] The stage of complete self-discipline, although sometimes brought into wavering through negligence. |

| 7. Apramatta Sanyati | Complete observance of Mahavratas (Major Vows) |

| 8. Apūrvakaraņa | New channels of thought. |

| 9. Anivāttibādara-sāmparāya | Advanced thought-activity |

| 10. Sukshma sāmparāya | Slight greed left to be controlled or destroyed. |

| 11. Upaśānta-kasāya | The passions are still associated with the soul, but they are temporarily out of effect on the soul. |

| 12. Ksīna kasāya | Desirelessness, i.e., complete eradication of greed |

| 13. Sayoga kevali (Arihant) | Omniscience with vibrations. Sa means "with" and yoga refers to the three channels of activity, i.e., mind, speech and body.[119] |

| 14. Ayoga kevali | The stage of omniscience without any activity. This stage is followed by the soul's destruction of the aghātiā karmas. |

At the second-to-last stage, a soul destroys all inimical karmas, including the knowledge-obscuring karma which results in the manifestation of infinite knowledge (Kevala Jnana), which is said to be the true nature of every soul.[120]

Those who pass the last stage are called Siddha and become fully established in Right Faith, Right Knowledge and Right Conduct.[121] According to Jain texts, after the total destruction of karmas the released pure soul (Siddha) goes up to the summit of universe (Siddhashila) and dwells there in eternal bliss.[122]

The soul removes its ignorance (mithyatva) at the 4th stage, vowlessness (avirati) at the 6th stage, passions (kashaya) at the 12th stage, and yoga (activities of body, mind and speech) at the 14th stage, and thus attains liberation.[123]

God[edit]

Main article: God in Jainism

See also: Pañca-Parameṣṭhi

Jain texts reject the idea of a creator or destroyer God and postulate an eternal universe. Jain cosmology divides the worldly cycle of time into two parts (avasarpiṇī and utsarpiṇī). According to Jain belief, in every half-cycle of time, twenty-four Tīrthaṅkaras grace this part of the Universe to teach the unchanging doctrine of right faith, right knowledge and right conduct.[124][125][126] The word tīrthankara signifies the founder of a tirtha, which means a fordable passage across a sea. The Tīrthaṅkaras show the 'fordable path' across the sea of interminable births and deaths.[127] Rishabhanatha is said to be the first Tīrthankara of the present half-cycle (avasarpiṇī). Mahāvīra (6th century BC) is revered as the last tīrthankara of avasarpiṇī.[128][129] Though Jain texts explain that Jainism has always existed and will always exist,[98] modern historians place the earliest evidence of Jainism in the 9th century BC.[130]

In Jainism, perfect souls with the body are called arihant ("victors") and perfect souls without the body are called Siddhas ("liberated souls"). Tirthankara is an arihant who helps others to achieve liberation. Tirthankaras become role models for those seeking liberation. They are also called human spiritual guides.[131] They reorganise the four-fold order that consists of muni ("male ascetics'), aryika ("female ascetics"), śrāvaka ("laymen"), and śrāvikā ("laywoman").[132][133] Jainism has been described as a transtheistic religion,[134] as it does not teach dependency on any supreme being for enlightenment. The tirthankara is a guide and teacher who points the way to enlightenment, but the struggle for enlightenment is one's own. The following two verses of the Ratnakaranda śrāvakācāra expound the definition of God according to Jainism:[135]

History[edit]

Main article: History of Jainism

Origins[edit]

See also: Timeline of Jainism and Śramaṇa

The origins of Jainism are obscure.[136][137] Jainism is a philosophy of eternity, and Jains believe their religion to be eternal.[138][139][98] Ṛṣabhanātha is said to be the founder of Jainism in the present half cycle.[140] Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan, the first Vice President of India wrote:

Further, he believed that Jainism was much older than Hinduism:[142]

And in the first volume of The Cultural Heritage of India:[143]

Jains revere Vardhamana Mahāvīra (6th century BCE) as the twenty-fourth tirthankara of this era. He appears in the tradition as one who, from the beginning, had followed a religion established long ago.[144]

Parshvanatha, predecessor of Mahāvīra and the twenty-third tirthankara was a historical figure.[129][145] He lived in the 9th century BCE.[146][147][148]

On antiquity of Jainism, Dr. Heinrich Zimmer was of the view that:

There is inscriptional evidence for the presence of Jain monks in south India by the second or first centuries BC, and archaeological evidence of Jain monks in Saurashtra in Gujarat by the second century CE.[150]

Royal patronage[edit]

The ancient city Pithunda, capital of Kalinga (modern Odisha), is described in the Jain text Uttaradhyana Sutra as an important centre at the time of Mahāvīra, and was frequented by merchants from Champa.[151] Rishabhanatha, the first tirthankara, was revered and worshiped in Pithunda and was known as the Kalinga Jina. Mahapadma Nanda (c. 450 – 362 BCE) conquered Kalinga and took a statue of Rishabha from Pithunda to his capital in Magadha. Jainism is said to have flourished under the Nanda Empire.[152]

The Maurya Empire came to power after the downfall of the Nanda. According to tradition, the first Mauryan emperor, Chandragupta Maurya (c. 322–298 BCE), became a Jain in the latter part of his life. He was a disciple of Bhadrabahu, the last srut-kevali (knower of all "Jain Agamas"), who migrated to South India.[153] Samprati (c. 224–215 BCE) grandson of the Maurya emperor Ashoka, is said to have been converted to Jainism by a Jain monk named Suhastin.[154]After his conversion, he was credited with actively spreading Jainism to many parts of India and beyond, both by making it possible for monks to travel to barbarian lands, and by building and renovating thousands of temples and establishing millions of icons.[155] He ruled a place called Ujjain.[156]

In the 1st century BCE, Emperor Kharavela, of the Mahameghavahana dynasty of Kalinga, invaded Magadha. He retrieved Rishabha's statue and installed it in Udaygiri, near his capital Shishupalgadh.[157] According to Michael Tobias, he was a Jain ruler, who was also a military victor.[158] However, according to Helmuth von Glasenapp, this cannot be said with certainty: Kharavela was probably a free-thinker who patronized all his subjects, including Jains.[159]

Xuanzang (629 – 645 CE), a Chinese traveller, notes that there were numerous Jains present in Kalinga during his time.[159] The Udayagiri and Khandagiri Caves near Bhubaneswar, Odisha, are the only surviving stone Jain monuments in Orissa.[160] The earlier rock-cut Jain structure of beads with inscriptions and drip-ledges is the earliest Jain monument in the southern most part of India which was from the first century BC to the sixth century AD. The Jain caves at Chitharal near Kanyakumari is one such monument.[161]

King Vanaraja (c. 720 – 780 CE) of the Chawda dynasty in northern Gujarat, raised by a Jain monk named Silunga Suri, supported Jainism during his rule. The king of Kannauj Āma (c. 8th century CE) was converted to Jainism by Bappabhatti, a disciple of the famous Jain monk Siddhasena Divakara.[162] Most of the rulers of the Chaulukya dynasty of Gujarat were Shaivaite, although they also patronized Jainism. The dynasty's founder Mularaja is said to have built Mulavasatika temple for Digambara and the Mulanatha-Jinadeva temple for the Svetambara Jains.[163] The earliest of the Dilwara Temples were constructed during the reign of Bhima I. Kumarapala started patronizing Jainism at some point in his life, and the subsequent Jain accounts portray him as the last great royal patron of Jainism.[164] Bappabhatti also converted Vakpati, the friend of Āma who authored a famous Prakrit epic titled Gaudavaho.[165]

Decline[edit]

Once a major religion, Jainism declined due to a number of factors, including proselytising by other religious groups, persecution, withdrawal of royal patronage, sectarian fragmentation, and the absence of central leadership.[166] Since the time of Mahāvīra, Jainism faced rivalry with Buddhism and the various Hindu sects.[167] The Jains suffered isolated violent persecutions by these groups, but the main reason for the decline of their religion was the success of Hindu reformist movements.[168] Around the 7th century, Shaivism saw considerable growth at the expense of Jainism due to the efforts of the Shaivite saints like Sambandar and Appar.[169]

Royal patronage has been a key factor in the growth as well as decline of Jainism.[166] The Pallava king Mahendravarman I (600–630 CE) converted from Jainism to Shaivism under the influence of Appar.[170] His work Mattavilasa Prahasana ridicules certain Shaiva sects and the Buddhists and also expresses contempt towards Jain ascetics.[171] Sambandar converted the contemporary Pandya king to Shaivism. During the 11th century, Basava, a minister to the Jain king Bijjala, succeeded in converting numerous Jains to the Lingayat Shaivite sect. The Lingayats destroyed various temples belonging to Jains and adapted them to their use.[172] The Hoysala king Vishnuvardhana (c. 1108–1152 CE) became a follower of the Vaishnava sect under the influence of Ramanuja, after which Vaishnavism grew rapidly in what is now Karnataka.[173] As the Hindu sects grew, the Jains compromised by following Hindu rituals and customs and invoking Hindu deities in Jain literature.[172]

There are several legends about the massacre of Jains in ancient times. The Buddhist king Ashoka (304–232 BCE) is said to have ordered killings of 18,000 Jains or Ajivikas after someone drew a picture of Buddha bowing at the feet of Mahāvīra.[174][175][176] The Shaivite king Koon Pandiyan, who briefly converted to Jainism, is said to have ordered a massacre of 8,000 Jains after his re-conversion to Shaivism. However, these legends are not found in the Jain texts, and appear to be fabricated propaganda by Buddhists and Shaivites.[177][178] Such stories of destruction of one sect by another sect were common at the time, and were used as a way to prove the superiority of one sect over the other. Another such legend about Vishnuvardhana ordering the Jains to be crushed in an oil mill does not seem to be historically true.[179]

The decline of Jainism continued after the Muslim conquests on the Indian subcontinent. Muslims rulers, such as Mahmud Ghazni (1001), Mohammad Ghori (1175) and Ala-ud-din Muhammed Shah Khilji (1298) further oppressed the Jain community.[181] They vandalised idols and destroyed temples or converted them into mosques. They also burned Jain books and killed Jains. Some conversions were peaceful, however; Pir Mahabir Khamdayat (c. 13th century CE) is well known for his peaceful propagation of Islam.[181][a] As bankers and financiers, the Jains had significant impact on Muslim rulers, but they were rarely able to enter into a political discourse which was framed in Islamic categories.[182] The Jains also enjoyed amicable relations with the rulers of the tributary Vedic Hindu kingdoms during this period; however, their number and influence had diminished significantly due to their rivalry with the Shaivite and Vaisnavite sects.[172]

Community[edit]

Main article: Jain community

Followers of the path practised and preached by the Jinas are known as Jains.[3][183][184][91] The majority of Jains currently reside in India. With six to seven million followers worldwide,[185] Jainism is relatively small compared to major world religions. Jains form 0.37% of India's population. Most of them are concentrated in the states of Maharashtra (31.46% of Indian Jains), Rajasthan (13.97%), Gujarat (13.02%) and Madhya Pradesh (12.74%). Karnataka (9.89%), Uttar Pradesh (4.79%), Delhi (3.73%) and Tamil Nadu (2.01%) also have significant Jain populations.[186] Outside India, large Jain communities can be found in Europe and the United States. Smaller Jain communities also exist in Canada[187] and Kenya.[188]

Jains developed a system of philosophy and ethics that had a great impact on Indian culture. They have contributed to the culture and language in the Indian states of: Tamil Nadu, Karnataka, Gujarat, Rajasthan, and Maharashtra.[189]

Jains encourage their monastics to do research and obtain higher education. Monks and nuns, particularly in Rajasthan, have published numerous research monographs. According to the 2001 Indian census, (the last time this information was gathered), Jains have the highest degree of literacy of any religious community in India (94.1 percent), above the national average of 64.8 percent. The gap between male and female literacy is the lowest among Jains at 6.8% compared to the national average of 21% and work participation among men is also the highest at 55.2%.[190][191]

Schools and branches[edit]

Main article: Jain schools and branches

The Jain community is divided into two major denominations, Digambara and Śvētāmbara. Monks of the Digambara ("sky-clad") tradition do not wear clothes. Female monastics of the Digambara sect wear unstitched plain white sarees and are referred to as Aryikas. Śvētāmbara ("white-clad") monastics on the other hand, wear white seamless clothes.[192]

During Chandragupta Maurya's reign, Acharya Bhadrabahu, the last śruta-kevali (all knowing by hearsay, i.e. indirectly) predicted a twelve-year-long famine and moved to Karnataka with his disciples. Sthulabhadra, a pupil of Acharya Bhadrabahu, stayed in Magadha.[193] After the famine, when followers of Acharya Bhadrabahu returned, they found that those who had stayed at Magadha had started wearing white clothes, which was unacceptable to the others who remained naked.[194] This is how the Digambara and Śvētāmbara schism began, with the former being naked while the latter wore white clothes.[195] Digambara saw this as being opposed to the Jain tenets which, according to them, required complete nudity. Evidence of gymnosophists ("naked philosophers") in Greek records as early as the fourth century BCE supports the claim of the Digambaras that they have preserved the ancient Śramaṇa practice.[196]

The earliest record of Digambara beliefs is contained in the Prakrit Suttapahuda of the Digambara Acharya, Kundakunda (c. 2nd century CE).[197] Digambaras believe that Mahavira remained unmarried, whereas Śvētāmbara believe that Mahavira married a woman who bore him a daughter.[198] The two sects also differ on the origin of Trishala, Mahavira's mother.[198] The Śvētāmbaras believe women may attain liberation and that the Tirthankara Māllīnātha was female.[199]

Excavations at Mathura revealed Jain statues from the time of the Kushan Empire (c. 1st century CE). Tirthankara represented without clothes, and monks with cloth wrapped around the left arm, are identified as the Ardhaphalaka ("half-clothed") mentioned in texts. The Yapaniyas, believed to have originated from the Ardhaphalaka, followed Digambara nudity along with several Śvētāmbara beliefs.[200]

Digambar tradition is divided into two main monastic orders Mula Sangh and the Kashtha Sangh, both led by Bhattarakas. In opposition to Bhattarakas and some rituals, Digambara Terapanth emerged in the 17th century.[201]

Svetambara tradition is divided into Murtipujaka and Sthanakvasi. Sthanakvasi opposes idol worship. The sect emerged in the 17th century and was led by Lonka Shaha. Murtipujaka builds temples and worships idols.[202] Te Svetambara Terapanth emerged from Sthanakvasi as a reformist movement led by Acharya Bhikshu in 1760. This sect is also non-idolatrous.[203][204][205][206]

In 20th century, new religious movements around the teachings of Kanji Swami and Shrimad Rajchandra emerged.[207][208]

Jain literature[edit]

Main articles: Jain literature and Jain Agamas

After the attainment of omniscience, the tirthankara discourses in a divine preaching hall called samavasarana. The discourse delivered is called Śhrut Jnāna and comprises eleven angas and fourteen purvas.[209] The discourse is recorded by Ganadharas (chief disciples), and is composed of twelve angas ("departments"). It is generally represented by a tree with twelve branches.[210]

Historically, the Jain Agamas were based on the teachings of Mahāvīra, the last Tīrthankara of the present half cycle. The Agamas were memorised and passed on through the ages. They were lost because of famine that caused the death of several saints within a thousand years of Mahāvīra's death.[211] These comprise thirty-two works: eleven angās, twelve upanga āgamas, four chedasūtras, four mūlasūtras, and the last, a pratikraman, or Avashyak sūtra.[212]

The Digambara sect of Jainism maintains that the Agamas were lost during the same famine in which the purvas were lost. According to the Digambaras, Āchārya Bhutabali was the last ascetic who had partial knowledge of the original canon. Later on, some learned Āchāryas started to restore, compile, and put into written words the teachings of Mahāvīra, that were the subject matter of Aagamas.[213] In the first century CE, Āchārya Dharasen guided two Āchāryas, Āchārya Pushpadant and Āchārya Bhutabali, to put these teachings in written form. The two Āchāryas wrote Ṣaṭkhaṅḍāgama, among the oldest-known Digambara Jain texts, on palm leaves. Digambara texts are classified under four headings, namely: Pratham-anuyoga,[214] Charn-anuyoga,[215] Karan-anuyoga and Dravya-anuyoga (texts expounding reality, i.e. tattva).[216][217][218]

Some of the most famous Jain texts include Samayasara, Ratnakaranda śrāvakācāra, and Niyamasara.[219]

Some scholars believe that the author of the oldest extant work of literature in Tamil (3rd century BCE), the Tolkāppiyam, was a Jain.[220] The Tirukkuṛaḷ by Thiruvalluvar is considered to be the work of a Jain by scholars such as Ka. Naa. Subramanyam,[221]V. Kalyanasundarnar, Vaiyapuri Pillai,[222] and P. S. Sundaram.[223] It emphatically supports vegetarianism in chapter 26 and states that giving up animal sacrifice is worth more than a thousand offerings in fire in verse 259.[224]

The Nālaṭiyār (a famous Tamil poetic work)[225] was composed by Jain monks from South India in 100–500.[226]

The Silappatikaram, the earliest surviving epic in Tamil literature, was written by a Jain, Ilango Adigal.[227] This epic is a major work in Tamil literature, describing the historical events of its time and of the then-prevailing religions, Jainism, Buddhism, and Shaivism.[227]

According to George L. Hart, who holds the endowed Chair in Tamil Studies at the University of California, Berkeley, the legend of the Tamil Sangams or "literary assemblies" was based on the Jain sangham at Madurai: "There was a permanent Jaina assembly called a Sangha established about 604 A.D. in Madurai. It seems likely that this assembly was the model upon which tradition fabricated the Sangam legend."[228]

Jain scholars and poets authored Tamil classics of the Sangam period, such as the Cīvaka Cintāmaṇi[229] and Nālaṭiyār.[225] In the beginning of the mediaeval period, between the 9th and 13th centuries, Kannada authors were predominantly Jains and Lingayatis. Jains were the earliest known cultivators of Kannada literature, which they dominated until the 12th century.[230] Jains wrote about the Tīrthaṅkaras and other aspects of the faith. Adikavi Pampa is one of the greatest Kannada poets.[citation needed] Court poet to the Chalukya king Arikesari, a Rashtrakuta feudatory, he is best known for his Vikramarjuna Vijaya.[231]

No comments:

Post a Comment